Self-contained DirectX Raytracing tutorial

Most frustratingexisting DXR tutorials out there ask you to clone a Git

repository and/or download a premade library, then walk you through how to use

the thing you just downloaded instead of teaching you about DXR itself.

I got tired of not being able to link to something that explains just DXR

without any extra fluff and “helpful” custom abstractions, so here it goes.

This article walks you through setting up a self-contained program that does

DXR from absolute scratch.

No framework, no additional downloads, just pure “how do I use this API?”

reference material from main() to animation and some basic raytracing effects.

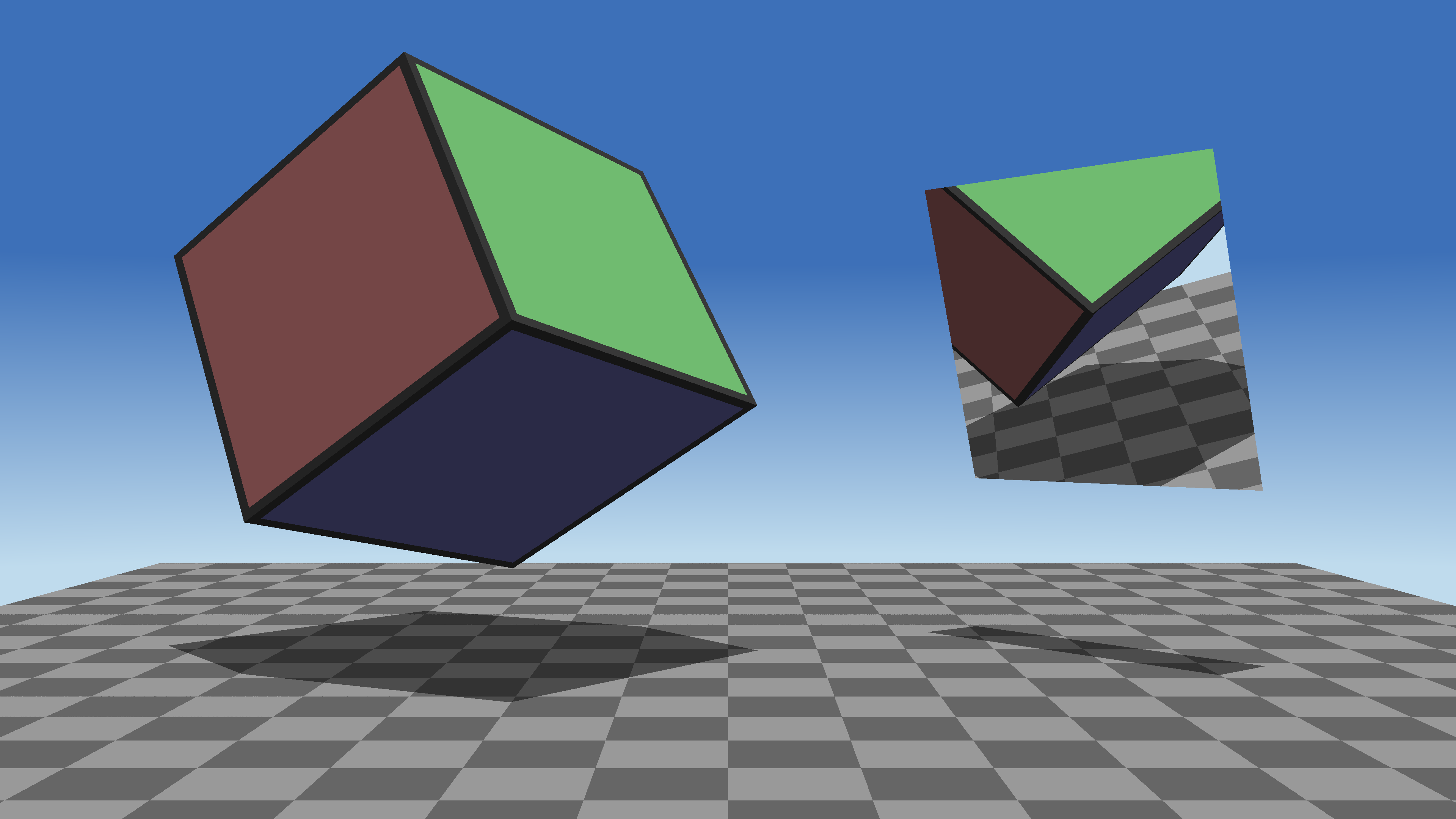

You’ll be able to read this article, copy-paste the code blocks in it from top to bottom, and end up with this 100% raytraced scene:

In fact, you can click to remove the article and explanations around the code blocks for unfettered copy-pasting.

Advanced C++ knowledge is assumed, along with some basic DX12. I’m also not covering what ray tracing is, how/why it works, or the necessary linear algebra. Although setting up and using DX12 will be part of the article in the name of being self-contained, it will help if you can already write a basic rasterized hello world DX12 cube, know the difference between a barrier and a fence, etc.

You’ll learn to:

- Write raytracing shaders in HLSL.

- Implement basic forms of raytracing effects, such as reflections and shadows.

- Set up a window and DX12 for rendering without using any helper library.

- Set up the resources and states in DX12 for dispatching rays.

- Build and update raytracing acceleration structures.

- Perform basic animation on static meshes in the raytracing pipeline.

- Render a fully raytraced scene.

What the code shown here is NOT:

- Promoting good practices or even okay practices. ComPtr<T> and error handling are for the weak.

- A foundation for your own fancier raytracing program. In the name of the first bullet point, I’ll be hardcoding many things.

- Performant. See above. I won’t bother with even the most basic optimizations to keep things short and straightforward.

- Reusable, extensible, or suitable for inclusion into a game engine, even a bad one. You get the idea.

If you want any of these, look for a rendering engine or a library. There are plenty that will have far better code quality at the cost of being harder to read for their DXR API usage alone.

That said, if you want to use snippets from this page for whatever reason, then unlike the rest of this blog, I’m licensing the code in this article under the WTFPL 2. All yours.

Requirements

You’ll need development tools for DirectX and C++ if you don’t have them already. The easiest way to get these is by installing “Game Development with C++” in Visual Studio 2022 or 2026 Community. This tutorial was written before VS2026 was released, but it will work with it. The DirectX 12 Agility SDK is not required.

If you’re not using Windows 11 version 24H2 or later, you must have a real GPU that supports at least DXR Tier 1.0.

These models support DXR from each major vendor:

- AMD: Radeon RX 6000 or newer support Tier 1.1.

- Intel: Arc A-series or newer support Tier 1.1.

- Nvidia: GeForce GTX 1000 cards support Tier 1.0. Anything RTX supports 1.1.

Windows 11 Version 24H2 added DXR Tier 1.1 support to WARP, which is always available, regardless of your GPU model (even with no GPU at all!). You’ll be able to use it by uncommenting one line of code shown later.

Tier 1.1 lets “traditional” shaders trace rays inline—such as a pixel shader dealing with its reflections—along with additional functionality missing from 1.0, like ExecuteIndirect being able to DispatchRays. This functionality will not be used in this article. As of writing, there are no tiers higher than 1.1.

Project setup

We’ll need one single C++20 source file and one HLSL file for the shaders. C++20 is mainly useful for designated initializers. We’ll make a LOT of structs, and D3DX12 is not part of the Windows SDK.

Follow one of the Raw or Visual Studio instructions, depending on your preference:

Raw

I promised that it would be from scratch. :)

Make these three files with your text editor of choice:

build.cmd

dxc shader.hlsl /T lib_6_3 /Fh shader.fxh /Vn compiledShader

cl program.cpp /nologo /std:c++20 /Zi

shader.hlsl

void dummy(){}

program.cpp

#include "shader.fxh" // To enforce an error if the shader didn't compile

int main(){}

Open x64 Native Tools Command Prompt for VS 2022 (or 2026) from your Start

menu, navigate to your project folder, and run build.cmd to end up with

program.exe.

Check if it works and runs before you proceed, then click here

to skip the next section.

Visual Studio

Make a new C++ console project, set the language version to C++20 on the .cpp file, add a .hlsl file to the solution, and edit its properties for All Configurations and All Platforms:

In General:

- Item type: HLSL Compiler

In HLSL Compiler→General:

- Shader Type: Library (/lib)

- Shader Model: Shader Model 6.3 (/6_3) (this will automatically use

dxc)

In HLSL Compiler→Output Files:

- Header Variable Name: compiledShader

- Header File Name: shader.fxh

To suppress a warning (for Debug only), in HLSL Compiler→Command Line→Additional Options:

- /Qembed_debug

You’ll want to be in Debug and x64 for now. Check if it compiles and runs.

Shader code

You probably noticed above that there is no raytracing shader type.

Shaders used with RT are compiled into a library, with “important” functions

marked with a [shader] attribute to indicate how they should be used in the

larger raytracing pipeline.

Three such shaders are mandatory:

Ray generation: These are similar to compute shaders in that you dispatch an

arbitrary 3D grid of them.

Closest hit: These are the ones that run if a ray hits something.

Miss: These are the ones that run if a ray didn’t hit anything.

There are other types, such as

Intersection (if you want custom intersection logic instead of ray-triangle),

Any hit (for transparent geometry), and

Callables (for virtual-like behavior).

Let’s ignore them for now.

These shaders communicate with each other through inout payload structures, so

let’s define ours.

Delete the contents of shader.hlsl, and let’s start writing it anew, for real

this time:

Payload structure

struct Payload

{

float3 color;

bool allowReflection;

bool missed;

};

color is obvious.

The other two flags will be used later to disable reflection on the mirror with

indirect bounces and to indicate if a ray missed geometry (for shadows).

Resources

We’ll also need to declare some resource bindings. The scene structure (also known as BVH, Bounding Volume Hierarchy) is the data structure that DXR uses to accelerate ray traversal. Its true contents are opaque from your point of view; there are dedicated commands to manage them. For this shader, it’s an SRV, but it’s otherwise mostly used with unordered access when it’s being built or updated.

RaytracingAccelerationStructure scene : register(t0);

The 2D texture where we’ll write the final color is a UAV though.

RWTexture2D<float4> uav : register(u0);

A real raytracer would need way more resources than the bare minimum shown here.

For instance, normal vectors for all the meshes contained in the BVH to compute

the direction of reflected rays.

SM6.6 ResourceDescriptorHeap can work wonders for this.

Constants

To avoid dealing with more resources or even a CBV, let’s hardcode a few things from the scene:

static const float3 camera = float3(0, 1.5, -7);

static const float3 light = float3(0, 200, 0);

static const float3 skyTop = float3(0.24, 0.44, 0.72);

static const float3 skyBottom = float3(0.75, 0.86, 0.93);

We’ll get transform matrices “for free” from raytracing intrinsics.

Ray generation

One of the Big Three raytracing shaders.

These shaders are dispatched from the CPU similarly to a compute shader, but

without [numthreads].

The name is arbitrary, but it has to be marked as a ray generation shader for HLSL. C++ will bind these shaders to the raytracing pipeline by name.

[shader("raygeneration")]

void RayGeneration()

{

Instead of getting the current shader index from a parameter marked with an SV

semantic, intrinsic functions need to be used (both of these return uint3):

uint2 idx = DispatchRaysIndex().xy;

float2 size = DispatchRaysDimensions().xy;

idx/size conveniently provides where the current ray belongs on the screen in

normalized [0,1) coordinates.

Let’s transform this into a vertical quad in the 3D world.

Its Y extent is 4 (camera.y ± 2), and its X extent depends on your screen aspect

ratio.

1.8 is an arbitrary number chosen to make the FOV look nice.

float2 uv = idx / size;

float3 target = float3((uv.x * 2 - 1) * 1.8 * (size.x / size.y),

(1 - uv.y) * 4 - 2 + camera.y,

0);

RayDesc is a built-in structure that describes a line segment as a

(start + direction * t) parametric equation.

TMin should be set to a small positive number to bias away from the emitter

(this is more relevant for bounces where there’s a danger of self-intersection,

but we’ll do it anyway), while TMax is where the trace is considered a miss,

with the appropriate shader being called.

RayDesc ray;

ray.Origin = camera;

ray.Direction = target - camera;

ray.TMin = 0.001;

ray.TMax = 1000;

Let’s also set up our custom payload struct: no color yet, reflections are allowed, and nothing has been missed so far. These flags will be used later.

Payload payload;

payload.allowReflection = true;

payload.missed = false;

It’s time for the main attraction: invoking the raytracing hardware!

Ignore the hardcoded arguments for now, what’s important for us is that we’re

tracing ray in the scene with the given inout payload.

TraceRay(scene, RAY_FLAG_NONE, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0, ray, payload);

For more information on TraceRay’s parameters, refer to the documentation. It’s very powerful for a shader intrinsic.

Once our ray has had its adventure, likely invoking multiple other shaders on its way, the final state of the payload is now available. This simple example writes it directly into the output texture, but it could be used to write a light map for caustics, store visibility information, etc.

This completes RayGeneration().

uav[idx] = float4(payload.color, 1);

}

Note that carrying local variables across a TraceRay call can be expensive.

They will likely need to be spilled out to VRAM and read back later.

Here, we’re only reading from the payload.

Miss

Miss shaders as opposed to mister shaders are invoked if a ray reaches

TMax without hitting anything.

Again, the name is arbitrary, but it has to be marked with [shader("miss")].

[shader("miss")]

void Miss(inout Payload payload)

{

A common use of these is to sample an environment map for a default fallback color. Let’s hardcode something like that based on the ray’s angle. 5 and 0.5 are arbitrary constants that place the gradient in a nice-looking spot.

float slope = normalize(WorldRayDirection()).y;

float t = saturate(slope * 5 + 0.5);

payload.color = lerp(skyBottom, skyTop, t);

If transparency was supported, we’d be blending payload.color instead of

overwriting it.

Let’s also record that this was a miss (it will be used elsewhere) and finish:

payload.missed = true;

}

Closest hit

Closest hit shaders run for rays that have successfully hit something. In our simple case, the closest hit is the only hit, as everything is opaque.

Let’s delegate what happens with each object in the demo scene to helper functions that we’ll write later:

void HitCube(inout Payload payload, float2 uv);

void HitMirror(inout Payload payload, float2 uv);

void HitFloor(inout Payload payload, float2 uv);

Unlike the other [shader]s, closest hit shaders take two parameters.

The first is the usual inout payload; the second is the output of the

intersection itself.

DXR comes with a highly-optimized ray-triangle intersection out of the box that

provides a float2 telling you where you are on the triangle with barycentric

weights

(0,0 = first vertex, 1,0 = second vertex, 0,1 = third vertex).

The weights are packed into the short-named

BuiltInTriangleIntersectionAttributes struct that you can unfortunately not

skip; you can’t ask for a float2 directly.

It’s predefined, and its only member is float2 barycentrics;.

[shader("closesthit")]

void ClosestHit(inout Payload payload,

BuiltInTriangleIntersectionAttributes attribs)

{

float2 uv = attribs.barycentrics;

DXR has some concept of objects in a scene. We’ll assign them identifiers later from C++, but for now, we can ask for this identifier using a built-in intrinsic function and delegate the work based on which object was hit:

switch (InstanceID())

{

case 0: HitCube(payload, uv); break;

case 1: HitMirror(payload, uv); break;

case 2: HitFloor(payload, uv); break;

This is pretty much enough already, but for safety (if you decide to tweak the source code, for instance), let’s indicate “anything else” with a bright, Unity-inspired error color.

default: payload.color = float3(1, 0, 1); break;

}

}

Cube

The scene has a rotating, diffuse cube. Let’s see which triangle of it got hit:

void HitCube(inout Payload payload, float2 uv)

{

uint tri = PrimitiveIndex();

This is a 0-based index into the object’s triangle list that we’ll provide later in C++. To get back to the vertices “properly”, we’d need to bind the vertex (and usually index) buffers as SRVs, but we skipped that earlier.

Instead, I’ll construct the vertex and index buffers in a particular order later in C++, so that the object-space normal vector can be conjured from just the index:

tri /= 2;

float3 normal = (tri.xxx % 3 == uint3(0, 1, 2)) * (tri < 3 ? -1 : 1);

This is just a visual trick, it’s not important to understand how it works.

You can replace it with float3 normal = 0.xxx; for a duller outcome.

Transforming this to world space is relatively simple: the transformation matrix is available “for free” through intrinsics. Since this is a normal vector, we’re not interested in the translation component.

float3 worldNormal = normalize(mul(normal, (float3x3)ObjectToWorld4x3()));

I also know in advance that the cube won’t be subject to non-uniform scaling. If you change that, you’ll need to use the inverse transpose of the matrix.

Let’s give the cube a look that’s not entirely uninteresting:

float3 color = abs(normal) / 3 + 0.5;

if (uv.x < 0.03 || uv.y < 0.03)

color = 0.25.rrr;

This is another visual trick that relies on foreknowledge of the index buffer’s

special properties, it’s not important to understand how it works.

You can remove the if and its body for a more traditional DirectX demo cube.

Let’s finish with some utterly fake and incorrect mockery of lighting, then record the final color in the payload to complete this function:

color *= saturate(dot(worldNormal, normalize(light))) + 0.33;

payload.color = color;

}

You can output float3(uv, 0) instead of color if you’d like to visualize the

barycentric coordinates.

Mirror

The cube demonstrated the use of a few intrinsics, but from a raytracing point of view, it’s utterly boring. Everything could’ve been achieved with a pixel shader and traditional UVs.

The rest of the objects will be more interesting and demonstrate one raytracing technique each. To no one’s surprise, the tilting mirror will be used for reflections.

Let’s start by respecting the payload flag that disables reflection. This will be used later on by shadows.

void HitMirror(inout Payload payload, float2 uv)

{

if (!payload.allowReflection)

return;

Use intrinsics to figure out where we are in the world and where a reflected ray

would go from here.

For this object, the object-space normal vector is always 0,1,0.

float3 pos = WorldRayOrigin() + WorldRayDirection() * RayTCurrent();

float3 normal = normalize(mul(float3(0, 1, 0), (float3x3)ObjectToWorld4x3()));

float3 reflected = reflect(normalize(WorldRayDirection()), normal);

Set up a new ray to trace the reflection:

RayDesc mirrorRay;

mirrorRay.Origin = pos;

mirrorRay.Direction = reflected;

mirrorRay.TMin = 0.001;

mirrorRay.TMax = 1000;

To be safe, disable further reflections to prevent an infinite recursion, although it’s not possible in this scene. You’re required to declare a maximum recursion count in C++, and going beyond that limit causes device removed.

payload.allowReflection = false;

TraceRay(scene, RAY_FLAG_NONE, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0, mirrorRay, payload);

There’s nothing to do after this; the final payload will be exactly the reflected payload. If the mirror had a tint, the color would need to be altered here, etc.

}

Floor

The next and last object in our demo scene is a floor that will demonstrate raytraced shadows.

Start writing its function, fetching world position:

void HitFloor(inout Payload payload, float2 uv)

{

float3 pos = WorldRayOrigin() + WorldRayDirection() * RayTCurrent();

Let’s use this to give the floor a checkerboard pattern so that it’s not entirely bland:

bool2 pattern = frac(pos.xz) > 0.5;

payload.color = (pattern.x ^ pattern.y ? 0.6 : 0.4).rrr;

To determine if this pixel should be in shadow, let’s trace a ray toward the

light source.

A TMax of 1 is enough here, since that means the ray is already at the light.

RayDesc shadowRay;

shadowRay.Origin = pos;

shadowRay.Direction = light - pos;

shadowRay.TMin = 0.001;

shadowRay.TMax = 1;

This ray has its own payload; we’re only interested in the missed flag from it.

Let’s disable reflections to consider the mirror opaque for shadows:

Payload shadow;

shadow.allowReflection = false;

shadow.missed = false;

TraceRay(scene, RAY_FLAG_NONE, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0, shadowRay, shadow);

Then, simply reduce brightness if the shadow ray hits anything before the light:

if (!shadow.missed)

payload.color /= 2;

}

With this, we’re done with the entire HLSL file! It’s time to write the program that uses it.

C++

Delete the contents of program.cpp.

Let’s start writing the real one.

#includes

Starting with a few macros to reduce global namespace pollution from Windows.h.

In particular, min and max macros would otherwise get #defined and break the

typed std::min and std::max.

#define NOMINMAX

#define WIN32_LEAN_AND_MEAN

#include <algorithm> // For std::size, typed std::max, etc.

#include <DirectXMath.h> // For XMMATRIX

#include <Windows.h> // To make a window, of course

#include <d3d12.h> // The star of our show :)

#include <dxgi1_4.h> // Needed to make the former two talk to each other

#include "shader.fxh" // The compiled shader binary, ready to go

In the spirit of minimalism, I won’t bother with separate linker options:

#pragma comment(lib, "user32") // For DefWindowProcW, etc.

#pragma comment(lib, "d3d12") // You'll never guess this one

#pragma comment(lib, "dxgi") // Another enigma

WndProc

This is our window’s event handler. As raw as it gets. Ultimately, everything is funneled back to the default handler of Windows, but we’ll handle the X button and the resizing of the window.

Resize will be implemented later to reallocate the render target according to

the window’s new resolution.

The initial resolution would be stretched over the window if this was not done.

void Resize(HWND);

LRESULT WINAPI WndProc(HWND hwnd, UINT msg, WPARAM wparam, LPARAM lparam)

{

switch (msg)

{

case WM_CLOSE:

case WM_DESTROY: PostQuitMessage(0); [[fallthrough]];

case WM_SIZING:

case WM_SIZE: Resize(hwnd); [[fallthrough]];

default: return DefWindowProcW(hwnd, msg, wparam, lparam);

}

}

Entry point

Time for a few more function declarations.

main only needs these two: one to set everything up, the other to keep

rendering frames.

void Init(HWND);

void Render();

Let’s start off by opting into the highest level of DPI awareness due to not having a manifest that would automatically do it (in the continued spirit of minimalism). This will make the window render actual pixels when running at >100% DPI. Otherwise Windows would scale a lower-resolution image up.

You might want to deliberately opt out with DPI_AWARENESS_CONTEXT_UNAWARE

if you have a high-DPI screen and a weak GPU, or planning to rely on software

emulation.

int main()

{

// Alternatively, DPI_AWARENESS_CONTEXT_UNAWARE

SetProcessDpiAwarenessContext(DPI_AWARENESS_CONTEXT_PER_MONITOR_AWARE_V2);

Next, let’s go through the motions to get a well-behaved window.

If your GPU is weak, or if you’re planning to rely on WARP, you’ll probably want

to make the window smaller than the default.

To do this, replace the last two CW_USEDEFAULT arguments with your desired

width and height.

For WARP, think really small, such as 320x240.

Emulation is slow.

This size is for the entire window, including its title bar, borders, etc.

WNDCLASSW wcw = {.lpfnWndProc = &WndProc,

.hCursor = LoadCursor(nullptr, IDC_ARROW),

.lpszClassName = L"DxrTutorialClass"};

RegisterClassW(&wcw);

HWND hwnd = CreateWindowExW(0, L"DxrTutorialClass", L"DXR tutorial",

WS_VISIBLE | WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

/*width=*/CW_USEDEFAULT, /*height=*/CW_USEDEFAULT,

nullptr, nullptr, nullptr, nullptr);

Initialize everything DirectX, now that there is a window that it can use.

Init(hwnd);

Run a traditional Windows message loop until a quit message is sent

(see WndProc calling PostQuitMessage).

for (MSG msg;;)

{

while (PeekMessageW(&msg, nullptr, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE))

{

if (msg.message == WM_QUIT)

return 0;

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessageW(&msg);

}

If there are no messages, keep calling Render.

That’s it for main!

Render(); // Render the next frame

}

}

Initialization

There is a LOT to do, so let’s split Init into a few other functions.

void Init(HWND hwnd)

{

#define DECLARE_AND_CALL(fn) void fn(); fn()

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitDevice);

void InitSurfaces(HWND); InitSurfaces(hwnd);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitCommand);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitMeshes);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitBottomLevel);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitScene);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitTopLevel);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitRootSignature);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitPipeline);

DECLARE_AND_CALL(InitShaderTables);

#undef DECLARE_AND_CALL

}

Let’s define a few constants that will be used often. In the interest of brevity, I’m skipping some fields from these structs throughout the article. Designated initialization will zero-initialize everything that’s not specified, which will commonly be used to default to “unknown”, “unused”, or “no flags”.

It’s easy to find documentation for these structs: simply place your text cursor (caret) in the struct’s name in VS and press F1 for MSDN or F12 to jump to its definition.

constexpr DXGI_SAMPLE_DESC NO_AA = {.Count = 1, .Quality = 0};

constexpr D3D12_HEAP_PROPERTIES UPLOAD_HEAP = {.Type = D3D12_HEAP_TYPE_UPLOAD};

constexpr D3D12_HEAP_PROPERTIES DEFAULT_HEAP = {.Type = D3D12_HEAP_TYPE_DEFAULT};

constexpr D3D12_RESOURCE_DESC BASIC_BUFFER_DESC = {

.Dimension = D3D12_RESOURCE_DIMENSION_BUFFER,

.Width = 0, // Will be changed in copies

.Height = 1,

.DepthOrArraySize = 1,

.MipLevels = 1,

.SampleDesc = NO_AA,

.Layout = D3D12_TEXTURE_LAYOUT_ROW_MAJOR};

Device

We’ll be creating these objects first, used to create any further resources and to submit and synchronize GPU commands:

IDXGIFactory4* factory;

ID3D12Device5* device;

ID3D12CommandQueue* cmdQueue;

ID3D12Fence* fence;

void InitDevice()

{

Let’s start by asking for a DXGI factory. Creating it in advance makes it easier to use WARP later.

We’ll try to create a factory with debugging and fall back to a regular one if it’s unavailable. This will be the case on PCs without the dev tools/SDK.

if (FAILED(CreateDXGIFactory2(DXGI_CREATE_FACTORY_DEBUG,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&factory))))

CreateDXGIFactory2(0, IID_PPV_ARGS(&factory));

Next, query for the availability of the D3D12 debug layer and activate it if present. This is technically not needed, but very useful if you decide to play around with the code. This needs to be done before D3D12CreateDevice, as turning the debug layer on or off will cause device removed.

if (ID3D12Debug* debug;

SUCCEEDED(D3D12GetDebugInterface(IID_PPV_ARGS(&debug))))

debug->EnableDebugLayer(), debug->Release();

Finally, let’s actually create the device. No GPU supports DXR but not feature level 12_1, so there’s no need to go lower than that.

If you want to use WARP, uncomment the EnumWarpAdapter line.

Feel free to bump the feature level up to 12_2 if you want to target DirectX 12 Ultimate on real hardware.

IDXGIAdapter* adapter = nullptr;

// Uncomment the following line to use software rendering with WARP:

// factory->EnumWarpAdapter(IID_PPV_ARGS(&adapter));

D3D12CreateDevice(adapter, D3D_FEATURE_LEVEL_12_1, IID_PPV_ARGS(&device));

A well-behaved program would query the device for its capabilities at this point because raytracing is optional in feature level 12_1. I’m skipping all that.

Let’s create the one and only command queue that this program will use instead:

D3D12_COMMAND_QUEUE_DESC cmdQueueDesc = {

.Type = D3D12_COMMAND_LIST_TYPE_DIRECT,

};

device->CreateCommandQueue(&cmdQueueDesc, IID_PPV_ARGS(&cmdQueue));

And a fence that will be used for GPU-CPU synchronization, completing this function:

device->CreateFence(0, D3D12_FENCE_FLAG_NONE, IID_PPV_ARGS(&fence));

}

In the continued spirit of minimalism, the only synchronization this fence will

ever be used for is a complete stall until everything is done on the GPU.

Let’s implement it right now.

Giving a nullptr to SetEventOnCompletion is an immediate, blocking wait, so

no CreateEventW call is needed.

void Flush()

{

static UINT64 value = 1;

cmdQueue->Signal(fence, value);

fence->SetEventOnCompletion(value++, nullptr);

}

Swap chain, UAV

We’ll be making these two next for the output pixels:

IDXGISwapChain3* swapChain;

ID3D12DescriptorHeap* uavHeap;

void InitSurfaces(HWND hwnd)

{

Let’s ask for a double-buffered swap chain for the window we made in main.

IDXGISwapChain3 provides GetCurrentBackBufferIndex that will be needed later,

but CreateSwapChainForHwnd returns IDXGISwapChain1.

DXGI_SWAP_CHAIN_DESC1 scDesc = {

.Format = DXGI_FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_UNORM,

.SampleDesc = NO_AA,

.BufferCount = 2,

.SwapEffect = DXGI_SWAP_EFFECT_FLIP_DISCARD,

};

IDXGISwapChain1* swapChain1;

factory->CreateSwapChainForHwnd(cmdQueue, hwnd, &scDesc, nullptr, nullptr,

&swapChain1);

swapChain1->QueryInterface(&swapChain);

swapChain1->Release();

The factory did its job, and it’s no longer needed:

factory->Release();

Due to DXGI not supporting UAVs for swap chains with DX12, we’ll need to make a

second surface with the exact same resolution.

It will be recreated all the time in Resize, so don’t bother creating it here,

but let’s allocate space for its UAV now:

D3D12_DESCRIPTOR_HEAP_DESC uavHeapDesc = {

.Type = D3D12_DESCRIPTOR_HEAP_TYPE_CBV_SRV_UAV,

.NumDescriptors = 1,

.Flags = D3D12_DESCRIPTOR_HEAP_FLAG_SHADER_VISIBLE};

device->CreateDescriptorHeap(&uavHeapDesc, IID_PPV_ARGS(&uavHeap));

Force a pretend resize to ensure the resource is made, and the UAV is valid. This completes this part of the setup.

Resize(hwnd);

}

Render target

Let’s continue with implementing Resize itself. WndProc will also call it, but way too early, so return if there’s nothing to resize just yet.

ID3D12Resource* renderTarget;

void Resize(HWND hwnd)

{

if (!swapChain) [[unlikely]]

return;

Query the client area (without the title bar, border, etc.) of the window for the resolution. Make sure it’s at least 1x1. DirectX doesn’t like 0-sized textures in any dimension (including depth).

RECT rect;

GetClientRect(hwnd, &rect);

auto width = std::max<UINT>(rect.right - rect.left, 1);

auto height = std::max<UINT>(rect.bottom - rect.top, 1);

Make sure that the GPU is not actively using these resources:

Flush();

Swap chains can be resized; they’ll deal with reallocations internally. ResizeBuffers will also handle entering/leaving fullscreen. DXGI handles Alt+Enter by default unless you opt out.

The first 0 and DXGI_FORMAT_UNKNOWN values mean to keep the existing properties of the swap chain.

swapChain->ResizeBuffers(0, width, height, DXGI_FORMAT_UNKNOWN, 0);

Our render target can’t be resized, so get rid of the old one first (except the very first time this function is called):

if (renderTarget) [[likely]]

renderTarget->Release();

Ask for a 2D texture having an identical resolution and pixel format to the swap chain so that it can be copied directly. Ask for UAV support for our shaders, and have it start in unordered access state, ready to use:

D3D12_RESOURCE_DESC rtDesc = {

.Dimension = D3D12_RESOURCE_DIMENSION_TEXTURE2D,

.Width = width,

.Height = height,

.DepthOrArraySize = 1,

.MipLevels = 1,

.Format = DXGI_FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_UNORM,

.SampleDesc = NO_AA,

.Flags = D3D12_RESOURCE_FLAG_ALLOW_UNORDERED_ACCESS};

device->CreateCommittedResource(&DEFAULT_HEAP, D3D12_HEAP_FLAG_NONE, &rtDesc,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_UNORDERED_ACCESS,

nullptr, IID_PPV_ARGS(&renderTarget));

Update the UAV in the heap that InitSurfaces made.

Since DX12 UAVs are values instead of IUnknowns, we can simply overwrite the old

one by creating a new one at the same address.

This concludes Resize.

D3D12_UNORDERED_ACCESS_VIEW_DESC uavDesc = {

.Format = DXGI_FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_UNORM,

.ViewDimension = D3D12_UAV_DIMENSION_TEXTURE2D};

device->CreateUnorderedAccessView(

renderTarget, nullptr, &uavDesc,

uavHeap->GetCPUDescriptorHandleForHeapStart());

}

Command list and allocator

Creating these is straightforward.

ID3D12GraphicsCommandList4 is the lowest version that supports raytracing.

ID3D12CommandAllocator* cmdAlloc;

ID3D12GraphicsCommandList4* cmdList;

void InitCommand()

{

device->CreateCommandAllocator(D3D12_COMMAND_LIST_TYPE_DIRECT,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&cmdAlloc));

device->CreateCommandList1(0, D3D12_COMMAND_LIST_TYPE_DIRECT,

D3D12_COMMAND_LIST_FLAG_NONE,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&cmdList));

}

Mesh data

Let’s hardcode a few meshes. “Quad” is a 2x2 horizontal XZ plane, while “Cube” is an indexed 2x2x2 cube around the origin. Why 2 and not 1? Because 1s were easier to type than 0.5s.

constexpr float quadVtx[] = {-1, 0, -1, -1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1,

-1, 0, -1, 1, 0, -1, 1, 0, 1};

constexpr float cubeVtx[] = {-1, -1, -1, 1, -1, -1, -1, 1, -1, 1, 1, -1,

-1, -1, 1, 1, -1, 1, -1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1};

constexpr short cubeIdx[] = {4, 6, 0, 2, 0, 6, 0, 1, 4, 5, 4, 1,

0, 2, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 3, 5, 7, 5, 3,

2, 6, 3, 7, 3, 6, 4, 5, 6, 7, 6, 5};

The index buffer has two non-obvious properties that the shaders abuse:

- Cube faces are ordered so that their normal vectors are -X, -Y, -Z, +X, +Y, +Z

- The first vertex of each triangle is opposite its hypotenuse

The quad vertices are ordered to make barycentrics contiguous across the entire surface. This is not used anywhere in the main article, but it can be useful in the appendix.

Mesh buffers

The meshes need to exist in GPU memory for GPU raytracing to see and use them, so let’s copy each array into a corresponding buffer:

ID3D12Resource* quadVB;

ID3D12Resource* cubeVB;

ID3D12Resource* cubeIB;

void InitMeshes()

{

These buffers will be nearly identical and worth a helper lambda.

The reference parameter is so that sizeof gives the size of the entire array.

auto makeAndCopy = [](auto& data) {

auto desc = BASIC_BUFFER_DESC;

desc.Width = sizeof(data);

ID3D12Resource* res;

device->CreateCommittedResource(&UPLOAD_HEAP, D3D12_HEAP_FLAG_NONE,

&desc, D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COMMON,

nullptr, IID_PPV_ARGS(&res));

Once the resource is made, we can map it and copy the array, completing the lambda.

void* ptr;

res->Map(0, nullptr, &ptr);

memcpy(ptr, data, sizeof(data));

res->Unmap(0, nullptr);

return res;

};

We simply need to call it for each array to implement InitMeshes:

quadVB = makeAndCopy(quadVtx);

cubeVB = makeAndCopy(cubeVtx);

cubeIB = makeAndCopy(cubeIdx);

}

Acceleration structures

For raytracing to work at a sensible FPS, your GPU needs space partitioning data for efficient geometry lookup. You don’t get to make these structures, but you’re responsible for allocating enough space for them, temp storage for their computation, and requesting the building or updating of these structures as appropriate.

The two kinds of structures we’ll be dealing with are the BLAS (Bottom Level Acceleration Structure) and TLAS (Top Level Acceleration Structure).

Simplified, a BLAS holds geometry, and a TLAS holds BLASes. You can think of a BLAS as corresponding to one mesh or object in the scene, but you’re not limited to this setup. It can be more efficient to merge multiple meshes into one BLAS.

You also don’t need to have the entire scene in one TLAS. A TLAS is just an SRV, and if you know where exactly you need to trace your rays, you could work in a reduced TLAS to further optimize things. An indoor game could limit its TLASes based on rooms in a dungeon, while an outdoor setup could do something similar to cascading shadow maps and trace a “far TLAS” if the “near TLAS” misses, assuming that most of the screen will show objects close to the player.

We’ll do none of these, and instead make 3 BLASes in 1 TLAS for our 3 objects in a very straightforward, hardcoded setup.

Acceleration structure building

Building a BLAS and a TLAS is very similar, so let’s start with a helper that does the common part.

Scratch space is dealt with for building the acceleration structures from scratch, but updating them needs a different amount of space. We’ll only need that for the TLAS in this example, so have it as an optional output:

ID3D12Resource* MakeAccelerationStructure(

const D3D12_BUILD_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_INPUTS& inputs,

UINT64* updateScratchSize = nullptr)

{

Let’s start with a helper that creates an unordered access buffer:

auto makeBuffer = [](UINT64 size, auto initialState) {

auto desc = BASIC_BUFFER_DESC;

desc.Width = size;

desc.Flags = D3D12_RESOURCE_FLAG_ALLOW_UNORDERED_ACCESS;

ID3D12Resource* buffer;

device->CreateCommittedResource(&DEFAULT_HEAP, D3D12_HEAP_FLAG_NONE,

&desc, initialState, nullptr,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&buffer));

return buffer;

};

First, we’ll need to ask how much space is required in these buffers. We’re not concerned with updating scratch data for now, so just pass it back to the caller.

D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_PREBUILD_INFO prebuildInfo;

device->GetRaytracingAccelerationStructurePrebuildInfo(&inputs,

&prebuildInfo);

if (updateScratchSize)

*updateScratchSize = prebuildInfo.UpdateScratchDataSizeInBytes;

Now that we know how big the buffers need to be, let’s create them. AS building requires them to be in a particular state at the start. The scratch space should be in UNORDERED_ACCESS state, but that’s invalid as the initial state of a buffer. COMMON works instead, no need for an explicit barrier.

Acceleration structures have a dedicated resource state.

auto* scratch = makeBuffer(prebuildInfo.ScratchDataSizeInBytes,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COMMON);

auto* as = makeBuffer(prebuildInfo.ResultDataMaxSizeInBytes,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE);

We can now place the inputs struct into a larger build description struct, complete with pointers to the buffers.

D3D12_BUILD_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_DESC buildDesc = {

.DestAccelerationStructureData = as->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

.Inputs = inputs,

.ScratchAccelerationStructureData = scratch->GetGPUVirtualAddress()};

Building is done through a command list. This is useful for updates: they can be pipelined after a compute shader, for instance.

cmdAlloc->Reset();

cmdList->Reset(cmdAlloc, nullptr);

cmdList->BuildRaytracingAccelerationStructure(&buildDesc, 0, nullptr);

cmdList->Close();

cmdQueue->ExecuteCommandLists(

1, reinterpret_cast<ID3D12CommandList**>(&cmdList));

On the other hand, we’ll completely stall the pipeline until building is done, then Release the scratch space in our continued quest for short and inefficient code. This concludes this helper function.

Flush();

scratch->Release();

return as;

}

BLAS

Let’s start by making another helper that takes a mesh and provides the

necessary struct for MakeAccelerationStructure that we just wrote.

It will support indexed and non-indexed meshes (i.e., the cube and the quad).

ID3D12Resource* MakeBLAS(ID3D12Resource* vertexBuffer, UINT vertexFloats,

ID3D12Resource* indexBuffer = nullptr, UINT indices = 0)

{

We’ll be using the built-in ray-triangle intersection functionality. Marking the mesh as opaque is good for performance as it can stop the search early.

D3D12_RAYTRACING_GEOMETRY_DESC geometryDesc = {

.Type = D3D12_RAYTRACING_GEOMETRY_TYPE_TRIANGLES,

.Flags = D3D12_RAYTRACING_GEOMETRY_FLAG_OPAQUE,

We’ll use the triangle half of the union (as opposed to AABBs with custom

intersection logic).

A transform matrix can be provided, but we’ll mark all of these as unused in the

BLASes, which is slightly more efficient.

.Triangles = {

.Transform3x4 = 0,

Feeding the rest of the mesh data to this struct is straightforward.

If vertices had other attributes than just a position, StrideInBytes would be

larger.

.IndexFormat = indexBuffer ? DXGI_FORMAT_R16_UINT : DXGI_FORMAT_UNKNOWN,

.VertexFormat = DXGI_FORMAT_R32G32B32_FLOAT,

.IndexCount = indices,

.VertexCount = vertexFloats / 3,

.IndexBuffer = indexBuffer ? indexBuffer->GetGPUVirtualAddress() : 0,

.VertexBuffer = {.StartAddress = vertexBuffer->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

.StrideInBytes = sizeof(float) * 3}}};

We’ll have just one piece of geometry per BLAS.

The

specification

lists official suggestions for Flags.

These won’t change, and we won’t bother with compaction, so ask for slow builds,

fast trace.

D3D12_BUILD_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_INPUTS inputs = {

.Type = D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BOTTOM_LEVEL,

.Flags = D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_BUILD_FLAG_PREFER_FAST_TRACE,

.NumDescs = 1,

.DescsLayout = D3D12_ELEMENTS_LAYOUT_ARRAY,

.pGeometryDescs = &geometryDesc};

All that’s left to do is to pass this struct to the common helper and reap the rewards.

return MakeAccelerationStructure(inputs);

}

The helper makes BLAS creation trivial:

ID3D12Resource* quadBlas;

ID3D12Resource* cubeBlas;

void InitBottomLevel()

{

quadBlas = MakeBLAS(quadVB, std::size(quadVtx));

cubeBlas = MakeBLAS(cubeVB, std::size(cubeVtx), cubeIB, std::size(cubeIdx));

}

TLAS

In the same vein as MakeBLAS, let’s make MakeTLAS.

We’ll be updating this every frame, so return the update scratch size as well.

ID3D12Resource* MakeTLAS(ID3D12Resource* instances, UINT numInstances,

UINT64* updateScratchSize)

{

An instance is a D3D12_RAYTRACING_INSTANCE_DESC struct in GPU memory. It represents an instance of a BLAS along with some user-provided ID numbers and mask bits that can be used for some flexibility for raytracing. All we used in the shaders was an object ID of 0, 1, or 2.

These structs will be dealt with later; for now they’re passed in as a parameter and go straight into the inputs struct. This one is optimized for neither fast builds nor fast trace, but it can be updated (=animated).

D3D12_BUILD_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_INPUTS inputs = {

.Type = D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_TYPE_TOP_LEVEL,

.Flags = D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_BUILD_FLAG_ALLOW_UPDATE,

.NumDescs = numInstances,

.DescsLayout = D3D12_ELEMENTS_LAYOUT_ARRAY,

.InstanceDescs = instances->GetGPUVirtualAddress()};

Call the MakeAccelerationStructure helper to create the TLAS itself, and we’re

done.

return MakeAccelerationStructure(inputs, updateScratchSize);

}

Instances

Time to allocate space for the D3D12_RAYTRACING_INSTANCE_DESC structs.

In the sample scene, we have exactly 3 objects directly corresponding to a BLAS each. The array indices will match the object IDs: [0]=cube, [1]=mirror, [2]=floor.

We’ll write a function that updates the Transform field of these later.

constexpr UINT NUM_INSTANCES = 3;

ID3D12Resource* instances;

D3D12_RAYTRACING_INSTANCE_DESC* instanceData;

void UpdateTransforms();

void InitScene()

{

Creating yet another buffer is straightforward, but we’ll use its CPU-mapped pointer differently than the others so far.

auto instancesDesc = BASIC_BUFFER_DESC;

instancesDesc.Width = sizeof(D3D12_RAYTRACING_INSTANCE_DESC) * NUM_INSTANCES;

device->CreateCommittedResource(&UPLOAD_HEAP, D3D12_HEAP_FLAG_NONE,

&instancesDesc, D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COMMON,

nullptr, IID_PPV_ARGS(&instances));

instances->Map(0, nullptr, reinterpret_cast<void**>(&instanceData));

Let’s initialize the constant parts of instanceData.

[0] is a cube, [1] and [2] are both quads.

for (UINT i = 0; i < NUM_INSTANCES; ++i)

instanceData[i] = {

.InstanceID = i,

.InstanceMask = 1,

.AccelerationStructure = (i ? quadBlas : cubeBlas)->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

};

To complete the structs with their transform matrices, force an update now:

UpdateTransforms();

We’re NOT calling Unmap, leaving instanceData mapped and writeable

forever.

}

Scene update

It’s time to compute those transform matrices.

Let’s start with a helper that converts from a 4x4 row-major XMMATRIX to the 3x4 layout that DXR wants. The documentation for these is confusing: both XMMATRIX and Transform claim to be row-major, but while XMMATRIX works for row vectors being on the left-hand side of multiplication, the DXR matrices follow OpenGL/Vulkan conventions and treat your position as a column vector that’s on the right-hand side.

You can think of them as 4x3 column-major matrices instead, which will be consistent, but in any case, an XMMATRIX needs to be transposed to be useful here. XMStoreFloat3x4 does that internally. XMMatrixTranspose + a memcpy for 12 floats would work just as well.

void UpdateTransforms()

{

using namespace DirectX;

auto set = [](int idx, XMMATRIX mx) {

auto* ptr = reinterpret_cast<XMFLOAT3X4*>(&instanceData[idx].Transform);

XMStoreFloat3x4(ptr, mx);

};

For simplicity™, the transform of everything will be a function of time with no interactivity.

auto time = static_cast<float>(GetTickCount64()) / 1000;

Have the cube perform an interesting rotation at these world coordinates:

auto cube = XMMatrixRotationRollPitchYaw(time / 2, time / 3, time / 5);

cube *= XMMatrixTranslation(-1.5, 2, 2);

set(0, cube);

Tilt the mirror towards the screen and a little down so that it will show the cube’s shadow, and then back and forth sideways over time:

auto mirror = XMMatrixRotationX(-1.8f);

mirror *= XMMatrixRotationY(XMScalarSinEst(time) / 8 + 1);

mirror *= XMMatrixTranslation(2, 2, 2);

set(1, mirror);

Make the floor large enough to cover everything and push it away from the camera:

auto floor = XMMatrixScaling(5, 5, 5);

floor *= XMMatrixTranslation(0, 0, 2);

set(2, floor);

Because instanceData is a permanently-mapped GPU resource, we’re already done.

}

TLAS

Now that the instance buffer is complete, we can build it into the TLAS. With all the helpers written so far, this is straightforward.

ID3D12Resource* tlas;

ID3D12Resource* tlasUpdateScratch;

void InitTopLevel()

{

UINT64 updateScratchSize;

tlas = MakeTLAS(instances, NUM_INSTANCES, &updateScratchSize);

Create the scratch space for TLAS updates in advance.

auto desc = BASIC_BUFFER_DESC;

// WARP bug workaround: use 8 if the required size was reported as less

desc.Width = std::max(updateScratchSize, 8ULL);

desc.Flags = D3D12_RESOURCE_FLAG_ALLOW_UNORDERED_ACCESS;

device->CreateCommittedResource(&DEFAULT_HEAP, D3D12_HEAP_FLAG_NONE, &desc,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COMMON, nullptr,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&tlasUpdateScratch));

}

Root signature

We’re finally free from acceleration structures! It’s time to work on giving them to the raytracing shaders. Let’s build a root signature for our PSO later.

ID3D12RootSignature* rootSignature;

void InitRootSignature()

{

2D typed UAVs can only be bound as part of a descriptor table, even if we only

have 1.

u0 will be the render target.

D3D12_DESCRIPTOR_RANGE uavRange = {

.RangeType = D3D12_DESCRIPTOR_RANGE_TYPE_UAV,

.NumDescriptors = 1,

};

D3D12_ROOT_PARAMETER params[] = {

{.ParameterType = D3D12_ROOT_PARAMETER_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_TABLE,

.DescriptorTable = {.NumDescriptorRanges = 1,

.pDescriptorRanges = &uavRange}},

The SRV in t0 will be the TLAS, and this is all we need in the root signature.

{.ParameterType = D3D12_ROOT_PARAMETER_TYPE_SRV,

.Descriptor = {.ShaderRegister = 0, .RegisterSpace = 0}}};

Not providing shader visibility flags (the defaulted zero) means that these are visible everywhere. Good enough!

The root signature doesn’t contain anything else but these parameters:

D3D12_ROOT_SIGNATURE_DESC desc = {.NumParameters = std::size(params),

.pParameters = params};

Go through the ritual of serializing this and creating the real root signature from its binary form.

ID3DBlob* blob;

D3D12SerializeRootSignature(&desc, D3D_ROOT_SIGNATURE_VERSION_1_0, &blob,

nullptr);

device->CreateRootSignature(0, blob->GetBufferPointer(),

blob->GetBufferSize(),

IID_PPV_ARGS(&rootSignature));

blob->Release();

}

Raytracing PSO

Raytracing PSOs have a different type that doesn’t inherit from

ID3D12PipelineState, because that would make too much sense.

ID3D12StateObject* pso;

void InitPipeline()

{

Microsoft loves reinventing PSO creation.

We have monolithic structs like D3D12_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_STATE_DESC,

a struct-of-structs with D3D12_PIPELINE_STATE_STREAM_DESC, and for this one,

an array-of-structs-with-pointers-to-structs in D3D12_STATE_OBJECT_DESC to

keep it new and exciting.

I can’t wait to see what they’ll come up with next week!

Let’s make the “inner” structs first.

This struct has fields to list exported shaders from the library. Not specifying any means exporting all of them.

D3D12_DXIL_LIBRARY_DESC lib = {

.DXILLibrary = {.pShaderBytecode = compiledShader,

.BytecodeLength = std::size(compiledShader)}};

The “hit” shaders (not just closest hit, but also any hit and intersection) must be packed into a hit group. The dispatched rays will refer to the hit group as a whole and not the individual shaders within.

D3D12_HIT_GROUP_DESC hitGroup = {.HitGroupExport = L"HitGroup",

.Type = D3D12_HIT_GROUP_TYPE_TRIANGLES,

.ClosestHitShaderImport = L"ClosestHit"};

Having multiple hit groups can be used to handle different types of materials.

A transparent or alpha-masked material would have an AnyHitShaderImport, for

instance.

sizeof(Payload) in the HLSL that we wrote is 20 (3+1+1 dwords).

The built-in ray-triangle intersection returns float2 barycentrics (2 dwords).

D3D12_RAYTRACING_SHADER_CONFIG shaderCfg = {

.MaxPayloadSizeInBytes = 20,

.MaxAttributeSizeInBytes = 8,

};

There are local root signatures for raytracing shaders individually, that this program doesn’t use at all; just one global root signature for everything. See the specification for further details.

D3D12_GLOBAL_ROOT_SIGNATURE globalSig = {rootSignature};

The maximum recursion limit has to be declared upfront, and going over this

causes device removed.

In the example scene, the longest possible bounce is

camera→¹mirror→²floor→³light.

D3D12_RAYTRACING_PIPELINE_CONFIG pipelineCfg = {.MaxTraceRecursionDepth = 3};

Pack these structs into the PSO description type du jour and create the object. This completes PSO creation.

D3D12_STATE_SUBOBJECT subobjects[] = {

{.Type = D3D12_STATE_SUBOBJECT_TYPE_DXIL_LIBRARY, .pDesc = &lib},

{.Type = D3D12_STATE_SUBOBJECT_TYPE_HIT_GROUP, .pDesc = &hitGroup},

{.Type = D3D12_STATE_SUBOBJECT_TYPE_RAYTRACING_SHADER_CONFIG, .pDesc = &shaderCfg},

{.Type = D3D12_STATE_SUBOBJECT_TYPE_GLOBAL_ROOT_SIGNATURE, .pDesc = &globalSig},

{.Type = D3D12_STATE_SUBOBJECT_TYPE_RAYTRACING_PIPELINE_CONFIG, .pDesc = &pipelineCfg}};

D3D12_STATE_OBJECT_DESC desc = {.Type = D3D12_STATE_OBJECT_TYPE_RAYTRACING_PIPELINE,

.NumSubobjects = std::size(subobjects),

.pSubobjects = subobjects};

device->CreateStateObject(&desc, IID_PPV_ARGS(&pso));

}

Shader tables

You might have noticed that the PSO is given the entire shader library.

DXR offers a lot of runtime flexibility: a program can use different shaders

within the same library on the CPU side without having to change PSO, and

TraceRay() in HLSL can affect what shaders run for each individual ray.

Predictably, this tutorial will use none of this flexibility, and we’ll instead hardcode the same 3 shaders all the time.

constexpr UINT64 NUM_SHADER_IDS = 3;

ID3D12Resource* shaderIDs;

void InitShaderTables()

{

A shader identifier is 32 bytes, but it must be aligned to 64 bytes, so simply allocate 64 bytes for each.

The 32 bytes of padding could be made useful and used for local root arguments. See the spec.

auto idDesc = BASIC_BUFFER_DESC;

idDesc.Width = NUM_SHADER_IDS * D3D12_RAYTRACING_SHADER_TABLE_BYTE_ALIGNMENT;

device->CreateCommittedResource(&UPLOAD_HEAP, D3D12_HEAP_FLAG_NONE, &idDesc,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COMMON, nullptr,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&shaderIDs));

Shader identifiers have to be queried from the PSO through another interface.

ID3D12StateObjectProperties* props;

pso->QueryInterface(&props);

Let’s make a helper that queries one shader identifier, writes it, and bumps the pointer forward:

void* data;

auto writeId = [&](const wchar_t* name) {

void* id = props->GetShaderIdentifier(name);

memcpy(data, id, D3D12_SHADER_IDENTIFIER_SIZE_IN_BYTES);

data = static_cast<char*>(data) +

D3D12_RAYTRACING_SHADER_TABLE_BYTE_ALIGNMENT;

};

Map the buffer for writing and write the shader IDs.

Note that ClosestHit is not used but rather the hit group it belongs to.

shaderIDs->Map(0, nullptr, &data);

writeId(L"RayGeneration");

writeId(L"Miss");

writeId(L"HitGroup");

shaderIDs->Unmap(0, nullptr);

Technically, this is one ID for ray generation, a 1-sized array of miss shader IDs, and another 1-sized array for the hit groups. Callables would go here, too, if we had any.

With this, this function is done, and we’re finally ready to dispatch rays.

props->Release();

}

TLAS update

Just one last thing before we get to actual, working raytracing. The transform matrices for the TLAS instances are permanently mapped into CPU space, but writing to them will have no effect until the TLAS is updated.

Let’s make a better update function that also updates the TLAS.

void UpdateScene()

{

UpdateTransforms();

Updating the TLAS is similar to building it, with two major differences. We’ll provide PERFORM_UPDATE as a build flag and a source acceleration structure. This can be the same address for an in-place update.

This helper will assume that the command list is already open.

D3D12_BUILD_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_DESC desc = {

.DestAccelerationStructureData = tlas->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

.Inputs = {

.Type = D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_TYPE_TOP_LEVEL,

.Flags = D3D12_RAYTRACING_ACCELERATION_STRUCTURE_BUILD_FLAG_PERFORM_UPDATE,

.NumDescs = NUM_INSTANCES,

.DescsLayout = D3D12_ELEMENTS_LAYOUT_ARRAY,

.InstanceDescs = instances->GetGPUVirtualAddress()},

.SourceAccelerationStructureData = tlas->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

.ScratchAccelerationStructureData = tlasUpdateScratch->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

};

cmdList->BuildRaytracingAccelerationStructure(&desc, 0, nullptr);

Updating the TLAS counts as a UAV access.

Make sure it’s done before the raytracing shaders attempt to use it.

We could Flush(), but that’s a little too extreme mid-frame (it does work,

though).

D3D12_RESOURCE_BARRIER barrier = {.Type = D3D12_RESOURCE_BARRIER_TYPE_UAV,

.UAV = {.pResource = tlas}};

cmdList->ResourceBarrier(1, &barrier);

}

We know that there will be nothing using the TLAS in a frame before this update, hence the lack of a UAV barrier before BuildRaytracingAccelerationStructure.

Command submission

It’s finally time to take everything we have made so far and trace some rays!

void Render()

{

Set state, bind resources

First, start building a command list. Not resetting the allocator would cause a memory leak, so do that, too:

cmdAlloc->Reset();

cmdList->Reset(cmdAlloc, nullptr);

Updating the TLAS is a GPU operation, so do it now with the command list open:

UpdateScene();

Set pipeline state and bind resources that will be used by the shaders.

By default, everything is resident, and our allocations are measured in kilobytes, so I’m skipping VRAM management altogether.

Raytracing counts as compute for resource binding purposes.

cmdList->SetPipelineState1(pso);

cmdList->SetComputeRootSignature(rootSignature);

cmdList->SetDescriptorHeaps(1, &uavHeap);

auto uavTable = uavHeap->GetGPUDescriptorHandleForHeapStart();

cmdList->SetComputeRootDescriptorTable(0, uavTable); // ←u0 ↓t0

cmdList->SetComputeRootShaderResourceView(1, tlas->GetGPUVirtualAddress());

DispatchRays

Ask the render target its current resolution.

This can change as the window gets resized.

We’ll emit 1 ray per pixel.

auto rtDesc = renderTarget->GetDesc();

To keep things fresh, DispatchRays packs all of its parameters into one huge struct.

We packed the shader records in exactly this order at offsets of 0, 64, 128. Everything is just one shader with no local root parameters (size = 32), and the tables only have 1 shader each.

D3D12_DISPATCH_RAYS_DESC dispatchDesc = {

.RayGenerationShaderRecord = {

.StartAddress = shaderIDs->GetGPUVirtualAddress(),

.SizeInBytes = D3D12_SHADER_IDENTIFIER_SIZE_IN_BYTES},

.MissShaderTable = {

.StartAddress = shaderIDs->GetGPUVirtualAddress() +

D3D12_RAYTRACING_SHADER_TABLE_BYTE_ALIGNMENT,

.SizeInBytes = D3D12_SHADER_IDENTIFIER_SIZE_IN_BYTES},

.HitGroupTable = {

.StartAddress = shaderIDs->GetGPUVirtualAddress() +

2 * D3D12_RAYTRACING_SHADER_TABLE_BYTE_ALIGNMENT,

.SizeInBytes = D3D12_SHADER_IDENTIFIER_SIZE_IN_BYTES},

.Width = static_cast<UINT>(rtDesc.Width),

.Height = rtDesc.Height,

.Depth = 1};

cmdList->DispatchRays(&dispatchDesc);

At this point, we have a nice raytraced image sitting in the wrong texture. We’ll need to copy it onto the swap chain’s current back buffer:

ID3D12Resource* backBuffer;

swapChain->GetBuffer(swapChain->GetCurrentBackBufferIndex(),

IID_PPV_ARGS(&backBuffer));

This will involve 4 barriers, which is worthy of a helper lambda.

auto barrier = [](auto* resource, auto before, auto after) {

D3D12_RESOURCE_BARRIER rb = {

.Type = D3D12_RESOURCE_BARRIER_TYPE_TRANSITION,

.Transition = {.pResource = resource,

.StateBefore = before,

.StateAfter = after},

};

cmdList->ResourceBarrier(1, &rb);

};

Start by transitioning the render target and back buffer to copy source/destination states.

barrier(renderTarget, D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_UNORDERED_ACCESS,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COPY_SOURCE);

barrier(backBuffer, D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_PRESENT,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COPY_DEST);

Do the copy.

cmdList->CopyResource(backBuffer, renderTarget);

Issue the same two barriers, but in reverse.

barrier(backBuffer, D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COPY_DEST,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_PRESENT);

barrier(renderTarget, D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_COPY_SOURCE,

D3D12_RESOURCE_STATE_UNORDERED_ACCESS);

Querying the back buffer added a reference to it. We don’t need it anymore:

backBuffer->Release();

Submit the command list to the GPU:

cmdList->Close();

cmdQueue->ExecuteCommandLists(

1, reinterpret_cast<ID3D12CommandList**>(&cmdList));

Present

Wait until everything is done (i.e., the image was copied) before Presenting it.

If you’re using overlays (like RivaTuner), those often hook Present. If you get warnings from the debug layer when calling this function, that will more often than not be caused by one of these.

Flush();

swapChain->Present(1, 0);

}

And that is it! The program should look similar to the image from the top of this article, but animated.

It should run well even on relatively weak GPUs, but reducing the window size can boost your FPS if you’re struggling. In that case, you might want to edit Resize to use half the RECT’s width and height for only ¼ the rays.

Appendix: Exercises

A few exercises that you can attempt if you wish to learn more about various topics, in rough order of increasing difficulty:

- Make the scene anti-aliased: trace multiple rays from RayGeneration() in slightly different directions (offset by half a pixel) and average the result.

- Make the cube’s 6 sides have 6 different colors (suggestion: RGBCMY)

- Make the mirror dirty: mix procedural noise with the reflected color. The quad vertex buffer’s ordering will help with this.

- Add a fourth object.

- Make AS generation slightly less horrible. You can query for all scratch space upfront, only allocate one buffer with the maximum size, and use UAV barriers between builds without a complete flush.

- Use CallShader() and callables for ClosestHit instead of a

switch. - Properly fetch vertex data (such as normals) from a vertex buffer.

- Don’t completely flush everything every frame. Start working on the next frame while the current one renders. You’ll need to duplicate a few resources to avoid contention.

- Implement proper light transport and global illumination.